HINDI RELATED CONTENT | WIKIPEDIA |

| |||

Linguistic history of India

This text from Wikipedia is available under the

Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License, additional terms may apply.

See Terms of Use

for details. Wikipedia« is a registered trademark of the

Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a

non-profit organization.

| |||

| | This section requires expansion. |

Dravidian languages

The Dravidian family of languages includes approximately 73 languages that are mainly spoken in southern India and northeastern Sri Lanka, as well as certain areas in Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, and eastern and central India, as well as in parts of Afghanistan and Iran, and overseas in other countries such as the UK, US, Canada, Malaysia and Singapore.

The origins of the Dravidian languages, as well as their subsequent development and the period of their differentiation, are unclear, and the situation is not helped by the lack of comparative linguistic research into the Dravidian languages. Inconclusive attempts have also been made to link the family with the Japonic languages and with the extinct Elamite language (Elamo-Dravidian hypothesis).

Legends common to many Dravidian-speaking groups speak of their origin in a vast, now-sunken continent far to the south. Many linguists, however, tend to favour the theory that speakers of Dravidian languages spread southwards and eastwards through the Indian subcontinent, based on the fact that the southern Dravidian languages show some signs of contact with linguistic groups which the northern Dravidian languages do not. Proto-Dravidian is thought to have differentiated into Proto-North Dravidian, Proto-Central Dravidian and Proto-South Dravidian around 1500 BCE, although some linguists have argued that the degree of differentiation between the sub-families points to an earlier split.

It was not until 1856 that Robert Caldwell published his Comparative grammar of the Dravidian or South-Indian family of languages, which considerably expanded the Dravidian umbrella and established it as one of the major language groups of the world. Caldwell coined the term "Dravidian" from the Sanskrit drāvida, related to the word ‘Tamil’ or ‘Tamilan’, which is seen in such forms as into ‘Dramila’, ‘Drami˜a’, ‘Dramida’ and ‘Dravida’ which was used in a 7th century text to refer to the languages of the south of India. The publication of the Dravidian etymological dictionary by T. Burrow and M. B. Emeneau was a landmark event in Dravidian linguistics.

History of Telugu

Origins

Telugu is hypothesised to have originated from a reconstructed Proto-Dravidian language. It is a highly Sanskritised language; as Telugu scholar C.P Brown states in page 266 of his book A Grammar of the Telugu language: "if we ever make any real progress in the language the student will require the aid of the Sanskrit Dictionary" . Inscriptions containing Telugu words dated back to 400 BCE were discovered in Bhattiprolu in District of Guntur. English translation of one inscription as reads: “Gift of the slab by venerable Midikilayakha".

Stages

It is possible to broadly define five stages in the linguistic history of the Telugu language:

400 BCE – 500 CE

Inscriptions in Telugu dating to 400 BCE were discovered in Bhattiprolu in the district of Guntur. The English translation of one inscription reads: “A gift of a slab by the venerable Midikilayakha.. The discovery of a Brahmi inscription reading Thambhaya Dhaanam as engraved on a soapstone reliquary is dated to the 2nd century BCE on paleographical grounds proves the antiquity of Telugu.

Primary sources are Sanskrit and Prakrit inscriptions found in the region, in which Telugu places and personal names are found. From this we know that the spoken vernacular was Telugu, while the rulers, who were of the Satavahana dynasty, used Prakrit in their monumental inscriptions. Telugu appears in the Gathasaptashathi Maharashtri Prakrit anthology of poems from the first century BCE from the Satavahana King Hala.

500 AD – 1100 AD

The first inscription that is entirely in Telugu corresponds to the second phase of Telugu history. This inscription, dated 575 CE, was found in the districts of Kadapa and Kurnool and is attributed to the Renati Cholas, who broke with the prevailing practice of using Prakrit and began writing royal proclamations in the local language. During the next fifty years, Telugu inscriptions appeared in Anantapuram and other neighboring regions. The earliest dated Telugu inscription from coastal Andhra Pradesh comes from about 633 CE.

Around the same time, the Chalukya kings of Telangana also began using Telugu for inscriptions. Telugu was more influenced by Sanskrit than Prakrit during this period, which corresponded to the advent of Telugu literature. This literature was initially found in inscriptions and poetry in the courts of the rulers, and later in written works such as Nannayya's Mahabharatam (1022 CE). During the time of Nannayya, the literary language diverged from the popular language. This was also a period of phonetic changes in the spoken language.

1100 CE – 1400 CE

The third phase is marked by further stylization and sophistication of the literary language. Ketana (13th century CE) in fact prohibited the use of the vernacular in poetic works. During this period the divergence of the Telugu script from the common Telugu-Kannada script took place. Tikkana wrote his works in this script.

1400 AD – 1900 AD

Telugu underwent a great deal of change (as did other Indian languages), progressing from medieval to modern. The language of the Telangana region started to split into a distinct dialect due to Muslim influence: Sultanate rule under the Tughlaq dynasty had been established earlier in the northern Deccan during the fourteenth century CE. South of the Krishna River (in the Rayalaseema region), however, the Vijayanagara empire gained dominance from 1336 CE till the late 1600s, reaching its peak during the rule of Krishnadevaraya in the sixteenth century, when Telugu literature experienced what is considered to be its golden age. Padakavithapithamaha, Annamayya, contributed many atcha (pristine) Telugu Padaalu to this great language. In the latter half of the seventeenth century, Muslim rule extended further south, culminating in the establishment of the princely state of Hyderabad by the Asaf Jah dynasty in 1724 CE. This heralded an era of Persian/Arabic influence on the Telugu language, especially on that spoken by the inhabitabts of Hyderabad. The effect is also felt in the prose of the early 19th century, as in the Kaifiyats.

1900 AD to date

The period of the late nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries saw the influence of the English language and modern communication/printing press as an effect of the British rule, especially in the areas that were part of the Madras Presidency. Literature from this time had a mix of classical and modern traditions and included works by scholars like Kandukuri Viresalingam and Panuganti Lakshminarasimha Rao.

Since the 1930s, what was considered an elite literary form of the Telugu language has now spread to the common people with the introduction of mass media like movies, television, radio and newspapers. This form of the language is also taught in schools as a standard. In the current decade the Telugu language, like other Indian languages, has undergone globalization due to the increasing settlement of Telugu-speaking people abroad. Modern Telugu movies, although still retaining their dramatic quality, are linguistically separate from post-Independence films.

At present, a committee of scholars have approved a classical language tag for Telugu based on its antiquity. The Indian government has also officially designated it as a classical language.

Carnatic music

Though Carnatic music (Karnataka sangitha) has a profound cultural influence on all of the South Indian States and their respective languages, most songs (Kirtanas) are in Kannada & Telugu. The region to the east of Tamil Nadu stretching from Tanjore in the south to Andhra Pradesh in the North was known as the Carnatic region during 17th & 18th Centuries. The Carnatic war in which Robert Clive annexed Trichirapali is relevant. The music that prevaled in this region during the 18th Century onwards was known as Carnatic Music. This is because the existing tradition is to a great extent an outgrowth of the musical life of the principality of Thanjavur in the Kaveri delta. Thanjavur was the heart of the Chola dynasty (from the 9th century to the 13th), but in the second quarter of the sixteenth century a Telugu Nayak viceroy (Raghunatha Nayaka) was appointed by the emperor of Vijayanagara, thus establishing a court whose language was Telugu. The Nayaks acted as governors of what is present day Tamil Nadu with their headquarters at Thanjavur (1530-1674 CE) and Madurai(1530-1781 CE). After the collapse of Vijayanagar, Thanjavur and Madurai Nayaks became independent and ruled for the next 150 years until they were replaced by Marathas. This was the period when several Telugu families migrated from Andhra and settled down in Thanjavur and Madurai. Most great composers of Carnatic music belonged to these families. Telugu, a language ending with vowels, giving it a mellifluous quality, was considered suitable for musical expression. Of the trinity of Carnatic music composers, Tyagaraja's and Syama Sastri's compositions were largely in Telugu, while Muttuswami Dikshitar is noted for his Sanskrit texts. Tyagaraja is remembered both for his devotion and the bhava of his krithi, a song form consisting of pallavi, (the first section of a song) anupallavi (a rhyming section that follows the pallavi) and charanam (a sung stanza which serves as a refrain for several passages in the composition). The texts of his kritis are almost all in Sanskrit, in Telugu (the contemporary language of the court). This use of a living language, as opposed to Sanskrit, the language of ritual, is in keeping with the bhakti ideal of the immediacy of devotion. Sri Syama Sastri, the oldest of the trinity, was taught Telugu and Sanskrit by his father, who was the pujari (Hindu priest) at the Meenakshi temple in Madurai. Syama Sastri's texts were largely composed in Telugu, widening their popular appeal. Some of his most famous compositions include the nine krithis, Navaratnamaalikā, in praise of the goddess Meenakshi at Madurai, and his eighteen krithi in praise of Kamakshi. As well as composing krithi, he is credited with turning the svarajati, originally used for dance, into a purely musical form.

History of Kannada

Kannada is one of the oldest Dravidian languages with an antiquity of at least 2000 years.[8] The spoken language is said to have separated from its proto-Dravidian source earlier than Tamil and about the same time as Tulu. However, archaeological evidence would indicate a written tradition for this language of around 1500–1600 years. The initial development of the Kannada language is similar to that of other Dravidian languages and independent of Sanskrit. During later centuries, Kannada has been greatly influenced by Tamil in terms of vocabulary, grammar and literary styles.

Stone inscriptions

The first written record in the Kannada language is traced to Emperor Ashoka's Brahmagiri edict dated 230 BC.[15] The first example of a full-length Kannada language stone inscription (shilashaasana) containing Brahmi characters with characteristics resembling those of Tamil in Hale Kannada (Old Kannada) script can be found in the Halmidi inscription, dated c. 450, indicating that Kannada had become an administrative language by this time.[17] Over 30,000 inscriptions written in the Kannada language have been discovered so far. The Chikkamagaluru inscription of 500 AD is another example.[21] Prior to the Halmidi inscription, there is an abundance of inscriptions containing Kannada words, phrases and sentences, proving its antiquity. The 543 AD Badami cliff shilashaasana of Pulakesi I is an example of a Sanskrit inscription in Hale Kannada script.[23]

Copper plates and manuscripts

Examples of early Sanskrit-Kannada bilingual copper plate inscriptions (tamarashaasana) are the Tumbula inscriptions of the Western Ganga Dynasty dated 444 A.D.[25] The earliest full-length Kannada tamarashaasana in Old Kannada script (early eighth century) belongs to Alupa King Aluvarasa II from Belmannu, South Kanara district and displays the double crested fish, his royal emblem. The oldest well-preserved palm leaf manuscript is in Old Kannada and is that of Dhavala, dated to around the ninth century, preserved in the Jain Bhandar, Mudbidri, Dakshina Kannada district. The manuscript contains 1478 leaves written in ink.

History of Tamil

Tamil has the one of the oldest literature amongst world languages , with epigraphic attestation dating to the 300 BC.

Literary works in India or Sri Lanka were preserved either in palm leaf manuscripts (implying repeated copying and recopying) or through oral transmission, making direct dating impossible. External chronological records and internal linguistic evidence, however, indicates that the oldest extant works were probably composed sometime between the 3rd century BC and the 2nd century AD.

The earliest extant text in Tamil is the Tolkāppiyam, a work on poetics and grammar which describes the language of the classical period, the oldest portions of this book may date back to around 300 BC . Preliminary results from archaeological excavations in 2005 suggest that the oldest inscriptions in Tamil may date at least to around 300 BC[1]. Apart from these, the earliest examples of Tamil writing we have today are rock inscriptions from the 3rd century BC, which are written in an adapted form of the Brahmi script (Mahadevan, 2003). Many Tamils argue in favour of a much earlier date for the literature by referring to Tamil legends of a lost continent, or by positing links to the Indus valley civilisation, the Sumerian Tammuz, and the Australian Kamilaroi, but none of these theories have been recognised by the mainstream scholarly community.

During the medieval period, a number of Sanskrit loan words were absorbed by Tamil, which many 20th century purists, notably Parithimaar Kalaignar and Maraimalai Adigal, later sought to remove. This movement was called thanith thamizh iyakkam (meaning pure Tamil movement). As a result of this, Tamil in formal documents, public speeches and scientific discourses is largely free of Sanskrit loan words. Between 800 and 1300, Malayalam is believed to have evolved from Tamil into a distinct language.

Languages of other families in India

Tibeto-Burman languages

Meitei language, Bodo language, Naga language, Garo language

Austro-Asiatic languages

The Austroasiatic family of languages includes the Santal and Munda languages of eastern India, Nepal, and Bangladesh, along with the Mon-Khmer languages spoken by the Khasi and Nicobarese in India and in Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, and southern China. The Austroasiatic languages are thought to have been spoken throughout the Indian subcontinent by hunter-gatherers who were later assimilated first by the agriculturalist Dravidian settlers and later by the Indo-Aryan peoples arriving from northwestern India.

The Austroasiatic family is thought to be the first to be spoken in ancient India. Some believe the family to be a part of an Austric superstock of languages, along with the Austronesian language family.

Indo-Pacific languages

According to Joseph Greenberg, the Andamanese languages of the Andaman Islands and the Nihali language of central India are thought to be Indo-Pacific languages related to the Papuan languages of New Guinea, Timor, Halmahera, New Britain,etc. Nihali has been shown to be related to Kusunda of central Nepal. However, the proposed Indo-Pacific relationship has not been established through the comparative method, and has been dismissed as speculation by most comparative linguists.

Nihali and Kusunda are spoken by hunting people living in forests. Both languages have accepted many loan words from other languages, Nihali having loans from Munda (Korku), Dravidian and Indic languages.

Evolution of scripts

Indus script

The term Indus script refers to short strings of symbols associated with the Harappan civilization of ancient India (most of the Indus sites are distributed in present-day Pakistan and northwest India) used between 2600–1900 BC, which evolved from an early Indus script attested from around 3500–3300 BC. They are most commonly associated with flat, rectangular stone tablets called seals, but they are also found on at least a dozen other materials. The first publication of a Harappan seal dates to 1875, in the form of a drawing by Alexander Cunningham. Since then, well over 4000 symbol-bearing objects have been discovered, some as far afield as Mesopotamia. After 1500 BC, use of the symbols ends, together with the final stage of Harappan civilization. There are over 400 different signs, but many are thought to be slight modifications or combinations of perhaps 200 'basic' signs. The symbols remain undeciphered (in spite of numerous attempts that did not find favour with the academic community), and most scholars tend to classify then as proto-writing rather than writing proper.

Brāhmī script

The best known inscriptions in Brāhmī are the rock-cut edicts of Ashoka, dating to the 3rd century BCE. These were long considered the earliest examples of Brāhmī writing, but recent archaeological evidence in Sri Lanka and Tamil Nadu suggest the dates for the earliest use of Brāhmī to be around the 6th century BCE, dated using radiocarbon and thermoluminescence dating methods.

This script is ancestral to most of the scripts of South Asia, Southeast Asia, Tibet, Mongolia, Manchuria, and perhaps even Korean Hangul. The Brāhmī numeral system is the ancestor of the Hindu-Arabic numerals, which are now used worldwide.

Brāhmī is generally believed to be derived from a Semitic script such as the Imperial Aramaic alphabet, as was clearly the case for the contemporary Kharosthi alphabet that arose in a part of northwest Indian under the control of the Achaemenid Empire. Rhys Davids suggests that writing may have been introduced to India from the Middle East by traders. Another possibility is with the Achaemenid conquest in the late 6th century BCE. It was often assumed that it was a planned invention under Ashoka as a prerequisite for the his edicts. Compare the much better documented parallel of the Hangul script.

Older examples of the Brahmi script appear to be on fragments of pottery from the trading town of Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka, which have been dated to the early 5th century BCE. Even earlier evidence of the Brahmi script has been discovered on pieces of pottery in Adichanallur, Tamil Nadu. Radio-carbon dating has established that they belonged to the 6th century BC. [2]

A minority position holds that Brāhmī was a purely indigenous development, perhaps with the Indus script as its predecessor; these include the English scholars G.R. Hunter and F. Raymond Allchin.

Kharoṣṭhī script

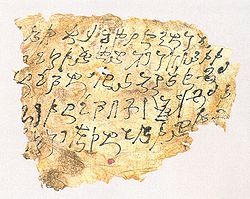

The Kharoṣṭhī script, also known as the Gāndhārī script, is an ancient abugida (a kind of alphabetic script) used by the Gandhara culture of ancient northwest India to write the Gāndhārī and Sanskrit languages. It was in use from the 4th century BCE until it died out in its homeland around the 3rd century CE. It was also in use along the Silk Road where there is some evidence it may have survived until the 7th century CE in the remote way stations of Khotan and Niya.

Scholars are not in agreement as to whether the Kharoṣṭhī script evolved gradually, or was the work of a mindful inventor. An analysis of the script forms shows a clear dependency on the Aramaic alphabet but with extensive modifications to support the sounds found in Indian languages. One model is that the Aramaic script arrived with the Achaemenid conquest of the region in 500 BCE and evolved over the next 200+ years to reach its final form by the 3rd century BCE. However, no Aramaic documents of any kind have survived from this period. Also intermediate forms have yet been found to confirm this evolutionary model, and rock and coins inscriptions from the 3rd century BCE onward show a unified and mature form.

The study of the Kharoṣṭhī script was recently invigorated by the discovery of the Gandharan Buddhist Texts, a set of birch-bark manuscripts written in Kharoṣṭhī, discovered near the Afghan city of Haḍḍā (compare Panjabi HAḌḌ ਹੱਡ s. m. "A bone, especially a big bone of dead cattle" referring to the famous mortuary grounds if the area): just west of the Khyber Pass. The manuscripts were donated to the British Library in 1994. The entire set of manuscripts are dated to the 1st century CE making them the oldest Buddhist manuscripts in existence.

Gupta script

The Gupta script was used for writing Sanskrit and is associated with the Gupta Empire of India which was a period of material prosperity and great religious and scientific developments. The Gupta script was descended from Brahmi and gave rise to the Siddham script.

Siddhaṃ script

Siddhaṃ (Sanskrit, accomplished or perfected), descended from the Brahmi script via the Gupta script, which also gave rise to the Devanāgarī script as well as a number of other Asian scripts such as Tibetan script.

Siddhaṃ is an abugida or alphasyllabary rather than an alphabet because each character indicates a syllable. If no other mark occurs then the short 'a' is assumed. Diacritic marks indicate the other vowels, the pure nasal (anusvara), and the aspirated vowel (visarga). A special mark (virama), can be used to indicate that the letter stands alone with no vowel which sometimes happens at the end of Sanskrit words. See links below for examples.

The writing of mantras and copying of Sutras using the Siddhaṃ script is still practiced in Shingon Buddhism in Japan but has died out in other places. It was Kūkai who introduced the Siddham script to Japan when he returned from China in 806, where he studied Sanskrit with Nalanda trained monks including one known as Praj˝ā. Sutras that were taken to China from India were written in a variety of scripts, but Siddham was one of the most important. By the time Kūkai learned this script the trading and pilgrimage routes over land to India, part of the Silk Road, were closed by the expanding Islamic empire of the Abbasids. Then in the middle of the 9th century there were a series of purges of "foreign religions" in China. This meant that Japan was cut off from the sources of Siddham texts. In time other scripts, particularly Devanagari replaced it in India, and so Japan was left as the only place where Siddham was preserved, although it was, and is only used for writing mantras and copying sutras.

Siddhaṃ was influential in the development of the Kana writing system, which is also associated with Kūkai – while the Kana shapes derive from Chinese characters, the princlple of a syllable-based script and their systematic ordering was taken over from Siddham.

Nagari script

Descended from the Siddham script around eleventh century.

LONWEB.ORG is a property of Casiraghi Jones Publishing srl

Owners: Roberto Casiraghi e Crystal Jones

Address: Piazzale Cadorna 10 - 20123 Milano - Italy

Tel. +39-02-78622122 email:

![]()

P.IVA e C. FISCALE 11603360154 • REA MILANO 1478561

Other company websites:

www.englishgratis.com

• www.scuolitalia.com